We can’t control the tides, but we can at least stop our students playing on the sandbars

We can’t control the tides, but we can at least stop our students playing on the sandbars

It seems incredible to say now, but I once received lessons in How To Google. And yesterday, Google rang the death-knell for that way of traditional searching.

Friday was Google’s annual I/O conference. Between the perennial updates to mobiles and tablets was arguably the most important innovation in search since PageRank: the opening up of their chatbot ‘Bard’, and the move to place it front and centre on the search results page.

It is fast, free, and extremely capable. And if we are not careful, it will destroy the way students use the Internet.

An uneasy alliance🔗

The relationship between teachers and the search-box has always been fraught.

Those old Google lessons on chuntering Pentium PCs were not just one-offs, they had whole carefully designed schemes of work about search operators, link assessing, citations, etcetera.

My dutiful I.C.T. teachers had grown up without the Internet: they were equal parts wary and awed by the power of this new ‘engine for search’. They - rightly - saw it for the fire-hose of information that it was, and recognised that students needed to be carefully introduced to the ‘right’ way to operate this powerful machine.

Without the proper training, it’ll drive you off an intellectual cliff, into a ravine of misinformation and misunderstanding. So each Thursday after lunch we sat in the computer lab, carefully typing search strings into the plain white box, scrolling down the page of blue linked search results.

An image from a happier time, when man and machine lived in perfect harmony and stock image providers were completely deranged.

An image from a happier time, when man and machine lived in perfect harmony and stock image providers were completely deranged.

Those lessons mattered because our teachers knew that, given half a chance, we’d simply click the first result we were given.

In this caution, however, lies the academic utility of Google: it was a librarian, pointing you towards sources of information; it was up to you to read, evaluate and extricate the information you needed from those sources. There’s a strong argument to be made that the ‘Google’ generation developed those essential academic skills of citation and synthesis far more quickly than previous, non-digitised students, simply by dint of having to wade through so many more potential sources. Skim-reading ten different webpages on the same topic is not a waste of time by any means, it’s the very point of being a scholar: to become immersed in the intellectual milieu of a subject, gradually forming one’s own unique perspective.

Now, I’m not so Panglossian as to suggest that all students, all the time, for all their work, used Google in this inquisitive, critical way. The point is that they could. With the right encouragement and scaffolding (and plagiarism vigilance) from their teachers, students could use Google as the incredible information democratiser that it was built to be.

Google’s mission is to “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. When handled with care, that purpose (specifically its first clause) made Google the most powerful tool in a student’s arsenal: laying a pathway to the answers they needed, but still requiring students to think to get the answer itself.

But that is no longer the case.

Zero-clicks, zero thought🔗

This is nothing new. Slowly, over the past decade, Google has been chipping away at that second clause: the “accessible and useful” part. Filtering through search results - for all its value as a learning exercise, is not “accessible.” Google’s expressed intention over the past few years has been to obfuscate that familiar list of blue links, turning from librarian to oracle.

Rich snippets and cards were one of the first attempts to turn search away from indexing sources of information to answering users’ queries directly. Rather than giving prominence at the top of the search page to the most relevant web pages, result cards snipped out what the algorithm decided was the relevant information, and plonked it directly in front of the searcher’s eyeballs.

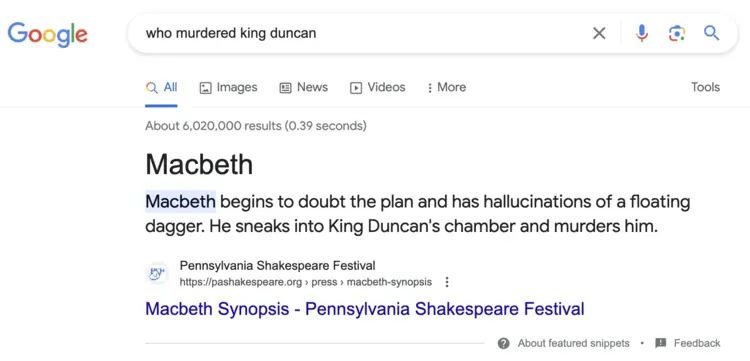

This is a rich snippet. Note that this still has a link - a digital paper trail for the diligent student to follow, evaluate and cite.

This is a rich snippet. Note that this still has a link - a digital paper trail for the diligent student to follow, evaluate and cite.

It’s a subtle shift, but one that marks a fundamental change in how we interact with search engines. It stops Google being a repository of potential answers - laid out for your to assess for yourself, as a scholar - to simply being the sole source of information in and of itself. This is the dream of ‘zero-click search’.

Friday’s announcement marks the next evolution of this philosophy, and it is far more troubling.

The ‘new generative search’ results page showcased by Google places AI-generated content at the very top: ahead of the traditional blue hyperlinks.

Whereas result cards at least had the decency to pull their information from a tangible source (with a link to read more if you were so inclined), the New Search aims to do away with the whole concept of ‘the source’. Through their LLM-power chatbot ‘Bard’, the Google will now generate brand new text to answer your query; text without a digital paper-trail, created through an opaque synthesisation of all the web’s writing.

It is no longer a ‘search engine’, but an answer engine.

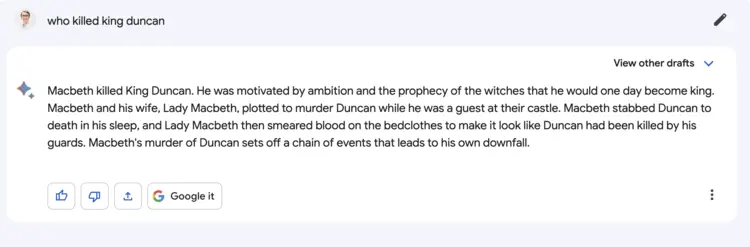

…and this is a ‘Bard’ response. No link, no citation, no paper trail: just pure unfiltered Information. There’s still a desultory ‘Google It’ button, of course, because how else will they pay for it?

…and this is a ‘Bard’ response. No link, no citation, no paper trail: just pure unfiltered Information. There’s still a desultory ‘Google It’ button, of course, because how else will they pay for it?

I’m feeling unlucky🔗

And the problem is: it will work. The answers provided will be (already are) lucid and convincing and good enough for the casual searcher. Because each response is generated, not indexed, it will also be next-to-impossible to detect as plagiarism. The usual reassurances have been given, but it’s an open secret that LLM-detection software is barely better than random.

There is no value to be found - not for schools, not for students - in a tool that simply gives answers. School is not about returning the right answer. Education is not about the tick-marks. Every perfect score isn’t a sign of success, it’s a marker of insufficient challenge and poorly scaled learning.

“Well done! You copied and pasted the answer I gave you. Here: have a Bachelors.”

“Well done! You copied and pasted the answer I gave you. Here: have a Bachelors.”

All this new product offers is danger; the danger that comes from automating and outsourcing the most important aspect of learning: getting things wrong and navigating the pathway to right-ness.

Imperfection is needed to trigger the learning journey, to enable thought. This idea is anathema to Google. Search will only ever move in one direction: whichever way removes the friction between user and product. ‘Thinking’ is just another piece of friction, grit in the gears of their well-oiled advertising machine.

So it falls to schools to take the step and recognise what is coming. And it needs to happen today, before our students become completely dependent on the incredible, infallible answer engine.

We can only pray for the return of the king.